Dr. Ala Stanford’s patient-care motto: ‘Take care of them like my own’

Ala Stanford, M.D., was born in North Philadelphia at Einstein Hospital to teenage parents. “When my father went off to college and my mother went to work in the suburbs, I was left to care for myself and my younger brother,” Dr. Stanford said.

“I was most happy when I was taking care of children,” said Dr. Stanford, who became the first Black female pediatric surgeon trained entirely in the U.S. “When I was a child, I wasn’t as protected by the adults in my life as I should have been. I later discovered that when I was able to take care of children and be their comforter and protector, I was healing my younger self.”

Taking care of people has become her life’s work, as both a caregiver and a doctor. “My great-grandmom lived to be 91, and I took care of her a lot,” she said. This care included making end-of-life decisions – from where she would live to whether to have a feeding tube inserted. “I realized that, in the end, people just want the people who love them to be around them and not to be in pain.”

Dr. Stanford is now recognized as a national leader in health equity and a health care policy from her years as an advisor to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. As a professor of practice at the University of Pennsylvania, with additional appointments in Perelman School of Medicine and Annenberg School of Communication, she is also working to shape the next generation of health care practitioners.

During her medical training, Dr. Stanford learned that health disparities are a major obstacle to health care equity. “My professors were saying that health outcomes weren’t good for people of color because they weren’t taking care of themselves,” she said. “They already brought that bias into the field through the classroom.”

That is why representation among health care providers matters. “Having a doctor that looks like them goes a long way to increasing quality of care,” she said. “There’s a shared cultural experience. Culturally, in Black and Latinx communities, there’s a reverence for older adults in making sure they are well cared for. When clinicians see older adults like their own family members, they take care of them accordingly.”

However, health care bias often includes ageism. “Some clinicians or health providers think that if a person is already 70, 80 or 90, then they’ve already lived a long life,” Dr. Stanford said. “So, all potential care options may not be discussed. That sometimes happens to older adults with their care delivery.”

Dr. Stanford had been a pediatric surgeon for 20 years, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and changed everything.

“People said that African Americans have COVID at a higher rate because they don’t go to the doctor and have chronic conditions,” Dr. Stanford said. “The truth is that Blacks were being turned away. They didn’t have access to care. That’s why I jumped in to help provide comfort and care.”

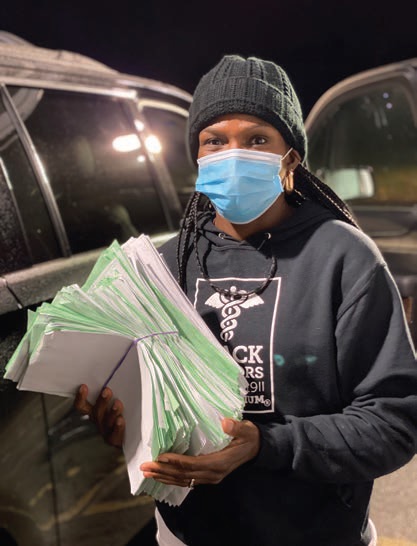

Dr. Stanford gained international recognition during the COVID-19 pandemic by using the infrastructure of her pediatric surgery practice to create The Black Doctors Consortium, a grassroots organization focused on education, testing, contact tracing and vaccination in communities devoid of access to care and resources. By focusing on individuals disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, her efforts helped to serve more than 100,000 people and saved countless lives.

“This idea that you have to wait for the money to come to do something cannot be repeated,” Dr. Stanford said. “With my savings and resources as a business owner, I was able to get us started while others were waiting for funds. It took some innovation and resourcefulness.”

When people were lined up during the pandemic for the COVID vaccine, Dr. Stanford made sure there were no older adults or people with disabilities waiting outside. “I brought them inside and gave them something to eat,” she said. “No one told me to do that. It wasn’t in a textbook. It was just the right thing to do. They never asked for anything or complained.”

Lessons learned from COVID

The pandemic put the lack of health care access in the national spotlight.

“You have to serve the vulnerable groups first,” Dr. Stanford said. “Resources need to be heavily weighted to provide access and services to those people. You must go to them.”

This way of thinking inspired Dr. Stanford to focus her efforts on eradicating health care disparities on a larger scale. In 2021, she opened the Dr. Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity (ASHE) in a North Philadelphia community with one of the lowest life expectancies in the city. The center, located at 2001 W. Lehigh Ave., provides expert health care and improves health outcomes for Philadelphians of all ages. (For more information: 484-270-6200 | bdccares.com)

“To increase health care access, there should be more ambulatory care centers that are associated with a church or with a community center, located in neighborhoods where older adults live,” Dr. Stanford said. “It’s important to have resources centrally located in one spot – behavioral health, insurance and benefits, primary care, blood draw, EKGs and vaccines. If it’s tough for you to get transportation, you can get everything done at once. That’s how to increase access and reduce health disparities.”

On Sept. 12, PCA presented Dr. Stanford with its inaugural Rodney D. Williams Award for Excellence in Service and Leadership. Both PCA and Dr. Stanford are committed to providing access to quality services through advocacy and education, as well as serving with empathy and care.

She will continue to be a trailblazer, forge new paths to advocate for the underserved and provide better health care to those who need it the most. Dr. Stanford wrote an autobiography, titled “Take Care of Them Like My Own: Faith, Fortitude and a Surgeon’s Fight for Health Justice,” to share her story with the wider public. She said: “If what you’re doing to work toward eradicating health care disparity isn’t uncomfortable, then you’re not doing enough.”